In David Lynch’s film Wild at Heart, women are demons or victims; they seem to have been constructed to fulfil certain archetypal male fantasies. The patterns defining the wicked witch/domineering mother and the victimised heroine/sexual temptress are specifically represented in the actions and physicality of the characters Lula and Marietta. Similarly, the men also might be perceived as archetypes; the Lover/Good Guy, the Libidinous Bad Guy/Evil Controller and the Innocent, all belong to the 1950’s melodrama.

If Lynch is parodying that genre, he is also reflecting the dominant macho culture that pervaded the post Second World War era. Although the film was made in 1991, Lynch seems untouched by the feminist movement which emerged at least a decade earlier.

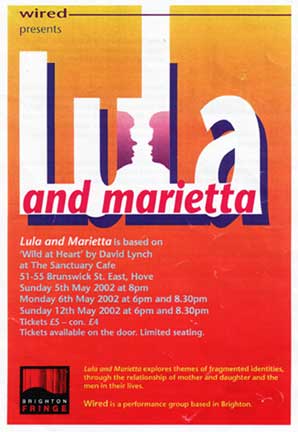

In this production whilst acknowledging the brilliant bravura of the film, WIRED aimed to redress the balance by offering alternative narratives to Lynch’s one-dimensional view of the complex relations between mother and daughter.

Excerpts from a review by Terry Hodgson

(Senior Lecturer Emeritus, Sussex University)

As one would expect, this was again a demanding and original production, worked through over a period of months. The material was drawn from David Lynch’s film Wild at Heart and aimed to reinvent the fundamental attitudes exhibited in the film, towards both men and women, which were seen as simplistic and archetypal.

Lynch, of course, was parodying but also exploiting a kind of melodrama, and cannot be accused of being unaware of the genre he is part guying. A straight melodrama would have been easier to rework, but then that would have been an easier target. Wild at Heart provided a complex base to work from.

In response, the company presented a series of permutations of relations between mother and daughter, played in different ways by different actresses (Witch, Madonna, Temptress etc), and drawing the audience into analysis of the varied possibilities.

The production raised the question of the difference between film and theatre. If film incorporates the viewer in the space but excludes him/her from the action, theatre incorporates the viewer more fully in the space and though not of course completely, in the action, because the challenge is physical, immediate and direct, especially if individual eye contact is made. In a close semi-circle, the problem for the actor is to maintain concentration in such circumstances. Different parts of the enclosing half circle were involved or excluded as the action shifted its focus and direction. The effect was disturbing and involving for audience as well as actors.

The reminiscence of filmic techniques of cutting, slow motion and stills, in the use of tableau, stylistic conventions and freeze, was extremely interesting. The mixture of dramatic styles invited a (semi)-detached Brechtian response to the characters without damaging the interest and dramatic tension.